Securing Liveability of Cities and Increasing Disaster Preparedness

How can cities adapt to climate extremes while fostering inclusive, democratic, and civil society-driven transformation?

This workshop explored how the city of Worms is adapting to climate extremes by activating civil society and welfare organizations. It was part of the Urban Transformation Conference 2025 and explored how cities can respond to climate extremes through inclusive, democratic, and civil society–driven approaches. Anchored in the experience of the City of Worms and the Ready4Heat project, the session showcased how municipalities can formalize networks, bridge administrative silos, and empower welfare

institutions, care facilities, and citizens to co-shape local climate adaptation. The Worms case, supported by the EU-funded Interreg Central Europe programme, served as a living lab for actor-centered heat adaptation, combining municipal policy anchoring with participatory network

governance.

Which stakeholders / actors need to be mobilized in order to achieve resilient cities?

Participants emphasized a broad, cross-sectoral coalition of stakeholders needed to mobilize and achieve a resilient city: municipal administration working transversally; multipliers such as churches, schools and sports clubs; companies (incl. construction sector) and local business associations; professional communicators/psychologists to “package” ideas; and hard-to-reach groups (migrantized communities, outdoor workers, people in ambulant care). “Low-hanging-fruit” institutions include senior-citizen homes and childcare; private landlords, the private housing sector and tenants’ associations were seen as pivotal for building-level measures. For urban land-use planning, participants listed planning/green/sewage departments, external planning offices, water suppliers, city council, municipal companies, educational institutions, private property owners, science, civil society, and project management. A recurrent point was to match specific projects with specific stakeholders rather than generic engagement. The Worms Heat Network formalizes this coalition via a charter and self-assessment, convening municipal units (environment, planning, social affairs), welfare providers and education institutions, and targeting seniors, daycare centres and outdoor workers with tailored formats (e.g., expert seminars, hotline pilots).

What measures – for quality of life or disaster prevention?

Participants called for a portfolio that couples immediate risk reduction with long-term liveability. Priorities should be informed by capacities actually needed, by currently covered scenarios, and by clarifying governance logics (top-down steering vs. bottom-up co-production). They recommended sequencing short-term and long-term actions, addressing disabling factors (institutional frictions, funding gaps), and minding the urban–rural interface and citizen–state fit. Blue-green (“sponge city”) measures were highlighted alongside social and organizational interventions; participants also discussed how to structure prioritization criteria transparently and communicate trade-offs. Urban Transformation Conference 2025 – Workshop Session

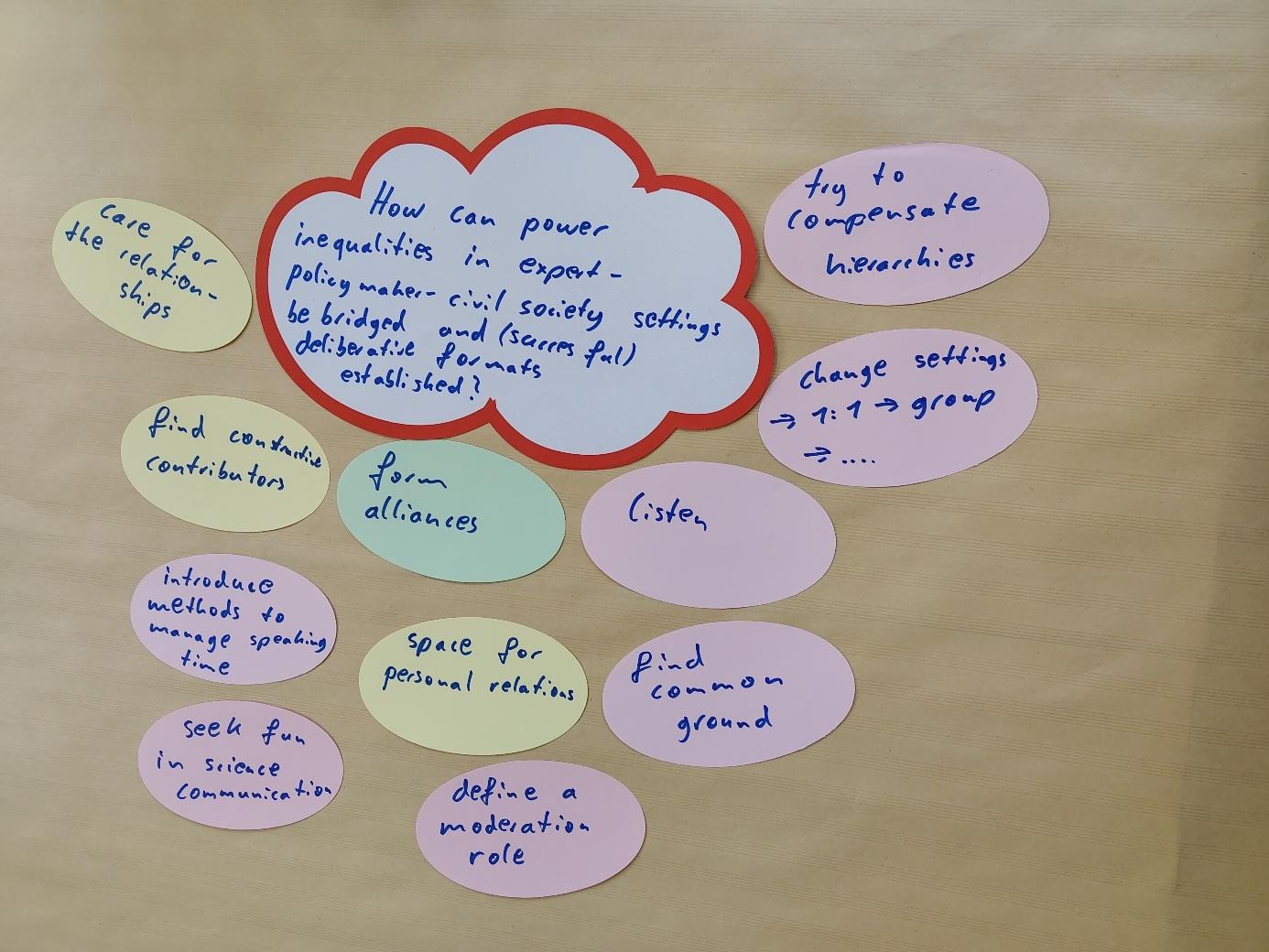

How can power inequalities in expert–policymaker–civil society settings be bridged and (successful) deliberative formats established?

Participants proposed relationship-centered facilitation: care for relationships, find constructive contributors, build alliances, and actively listen to establish common ground. They suggested compensating hierarchies by re-shaping settings (from 1:1 to group formats), introducing turn-taking/speaking-time methods, and creating space for personal relations. A moderation role should be explicit, and scientific communication should allow for enjoyment and accessibility to lower entry barriers. Overall, process design, rather than content alone, was seen as the key lever for equitable deliberation.

Which (social) innovations or tools can foster municipal cross-sectoral cooperation?

Participants suggested an implementation-oriented toolbox: interactive dashboards to track progress and responsibilities; routing tools (e.g., heat-avoiding pedestrian routing) that connect citizen experience with planning intelligence; networks and competence-building (e.g., grant-application skills); mixed municipality–topic teams for co-planning; participatory budgeting and carefully facilitated workshops; adapted citizens’ assemblies for equality; one-day idea labs with experts and young innovators; and explicit attention to accessibility/inclusivity. They also argued to learn from failure by documenting “what does not work and why” (e.g., an attempted vintners–kindergartens cooperation) and referenced design methods such as “Crafting Futures”. Worms operationalizes several of these ideas: Ready4Heat couples a network charter with self-assessment and stakeholder-specific benefits; partnerships with universities pilot heat-aware routing (HEAL) as both citizen service and planning input; and “fuck-up” reflections (e.g., re-scoping the vintners link) feed forward into new formats.

Across all discussions, participants agreed that technical solutions alone do not create resilience, it is the web of relationships, shared learning, and inclusive governance that transforms fragmented initiatives into transformative capacity. The workshop made visible how crucial intermediary actors are: individuals and organizations that translate between policy, practice, and lived experience. Building trust and cultivating an ethos of care within these interfaces, rather than enforcing formal coordination, was seen as the precondition for lasting collaboration. Another key lesson was the need to balance governance logics: municipalities should maintain strategic leadership while deliberately opening spaces for co-production with citizens, welfare institutions, and local businesses. Finally, several participants noted that acknowledging and analyzing failure can be as productive as showcasing success, as it exposes structural barriers that must be addressed for transformative adaptation. Looking ahead, participants envisioned climate adaptation as a learning system embedded in everyday municipal work. Strengthening feedback loops between science, policy, and civil society will be central, through shared data platforms, recurring cross-sectoral workshops, and participatory evaluation methods.